A culture bearer for his community, Jose has hope in our people and faith in our struggle for self-determination. Always gracious with his time, he teaches anyone who is open to listen. He’s been such a mentor to me and an inspiration for finding my own ways of engaging frontline communities here in Southern California. The first time I met José, he was protesting the Junta in Hato Rey and shared the history of Vieques with me. He was one of many activists that were arrested for protesting the U.S. Navy's occupation there. He told me of the families that were ravaged by disease from arms testing, and how the dumping of heavy metals and toxic chemicals seeped into the soil and water.

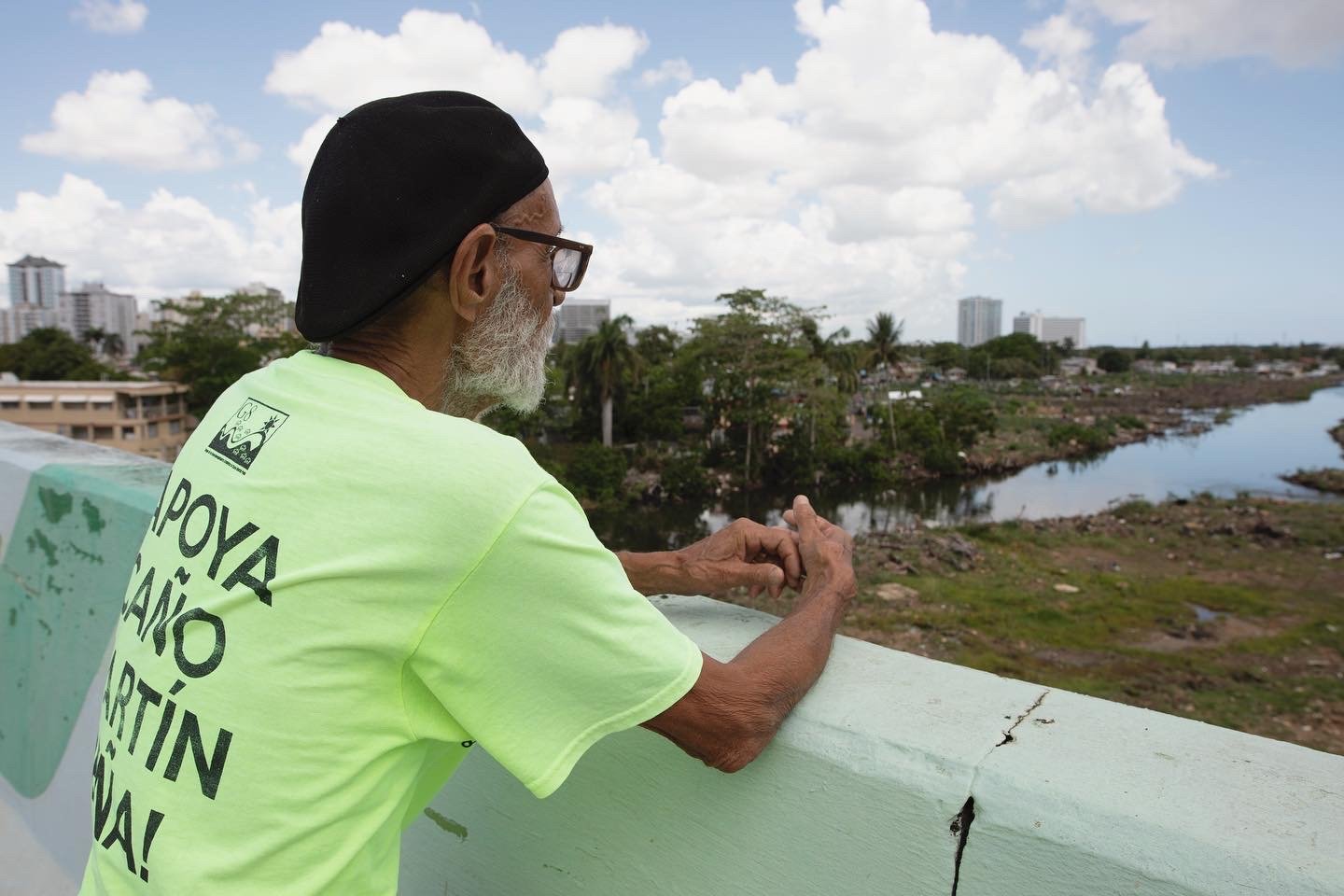

Our water is our life...everything flows from it. Jose knows about water and the ecosystems surrounding them. He’s a respected elder and community partner along Caño Martín Peña, he spends his days educating people on the challenges neighborhoods like his face systemically and ecologically.

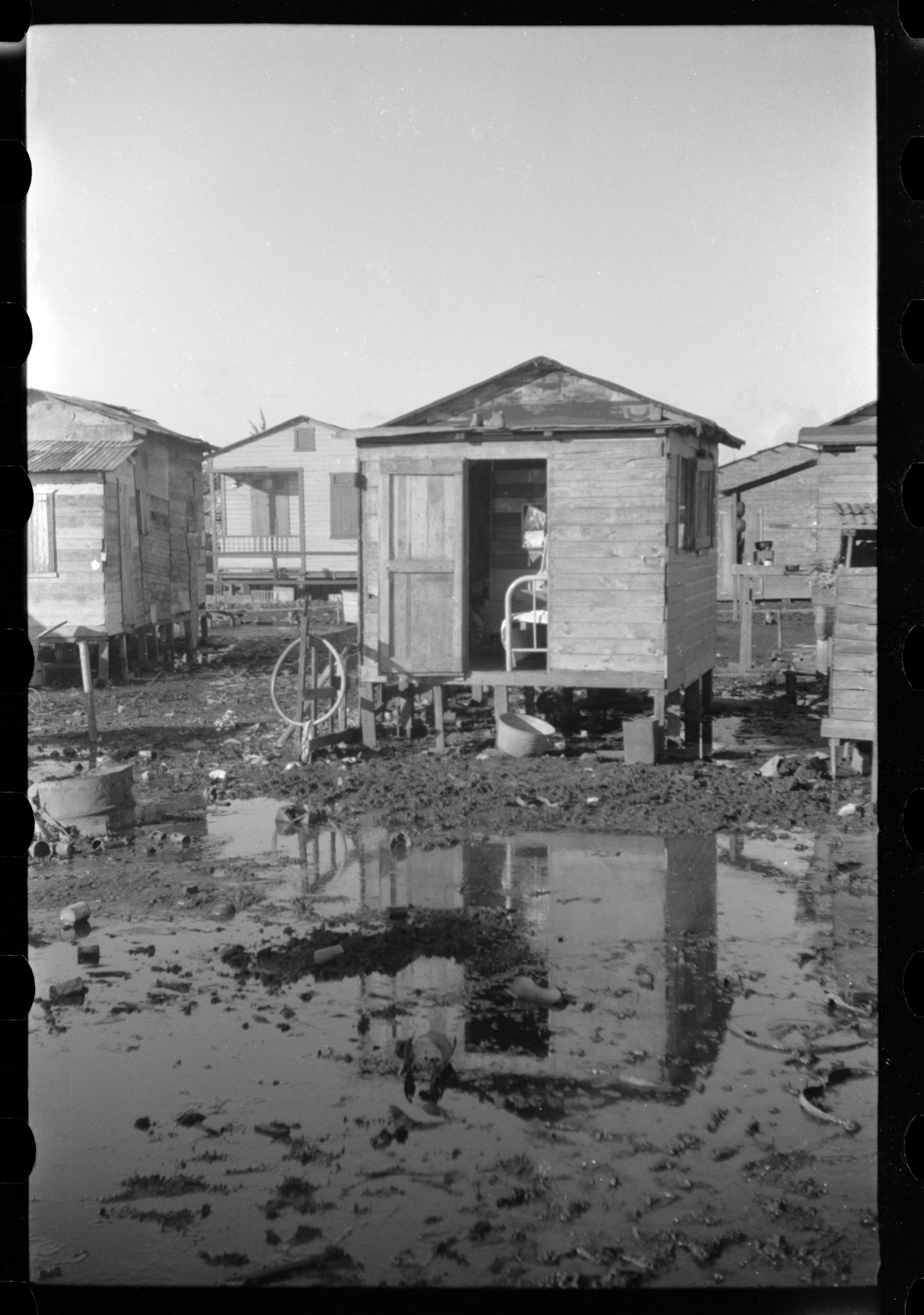

The Martín Peña Channel was once a waterway that ran through the middle of San Juan. In the thirties, thousands of families migrated from the mountains to the city to find work, transforming Puerto Rico's economy from rural agriculture to manufacturing as the sugar cane monoculture collapsed. This influx of residents and lack of city planning created squalid living conditions near the city and surrounding waterways. By the midcentury, those settlements along the channel, nicknamed "El Fanguito", were pushed out as the government tried to build a water system for transporting goods. Jose's father was one of many farmers that moved, lived in those slums and later purchased a home along the north of the waterway after government initiatives left families displaced. This is the home Jose lives in now.

Along the channel, eight neighborhoods that started as informal settlements now make up Jose's community. The current threat to area residents is that the water is not flowing in the channel and the stagnation is contaminating everything around it.

In 2002, the government proposed a new project to dredge and clean the channel. While this was a much needed proposal, locals were concerned that the improvements would drive up property values and gentrify the area, like so many other places in proximity to the city. Before they could fight to clean up the channel, they had to ensure their survival to avoid displacement. For over three years, organizers knocked on doors and got the buy in of residents to develop a community land trust, where the rights of the locals could be exercised over outside investors so everyone could have rights to the land.

While the success of this model inspired international acclaim, the G-8, or eight communities of Caño Martín Peña, are still fighting to clean their water system. After the hurricanes, the situation has become even more dire, as a third of the communities lack a sewer system, and the storm water system has collapsed. Recent federal allocations for flood control and recovery, managed by the Army Corps of Engineers, were withheld from funding the channel dredging project. They categorized the campaign as an ecological project with flood benefits instead of flood mitigation.

The struggle for environmental justice continues as Jose and his neighbors fight for their survival against higher prioritized rebuilding efforts.

Updated 9-2023

Everytime I go back, there are small developments. The last few images I took are of new housing being built in the community. Some of the residents of the land trust were given a choice to live in newly built homes (projects) along the channel that is being dredged and cleaned or they were offered an opportunity for a grant assisted home loan to move out of the area. Through much sadness, Jose, honoring his wife and children’s wishes, left the community he had lived in since he was a child for a less stressful living situation out of the city. He still returns weekly to the area and showed me the strides that younger organizers have made, but he said it was the hardest decision of his life.